Signal drifts of pigments and perception

Colour wheel designed by Goethe in 1809

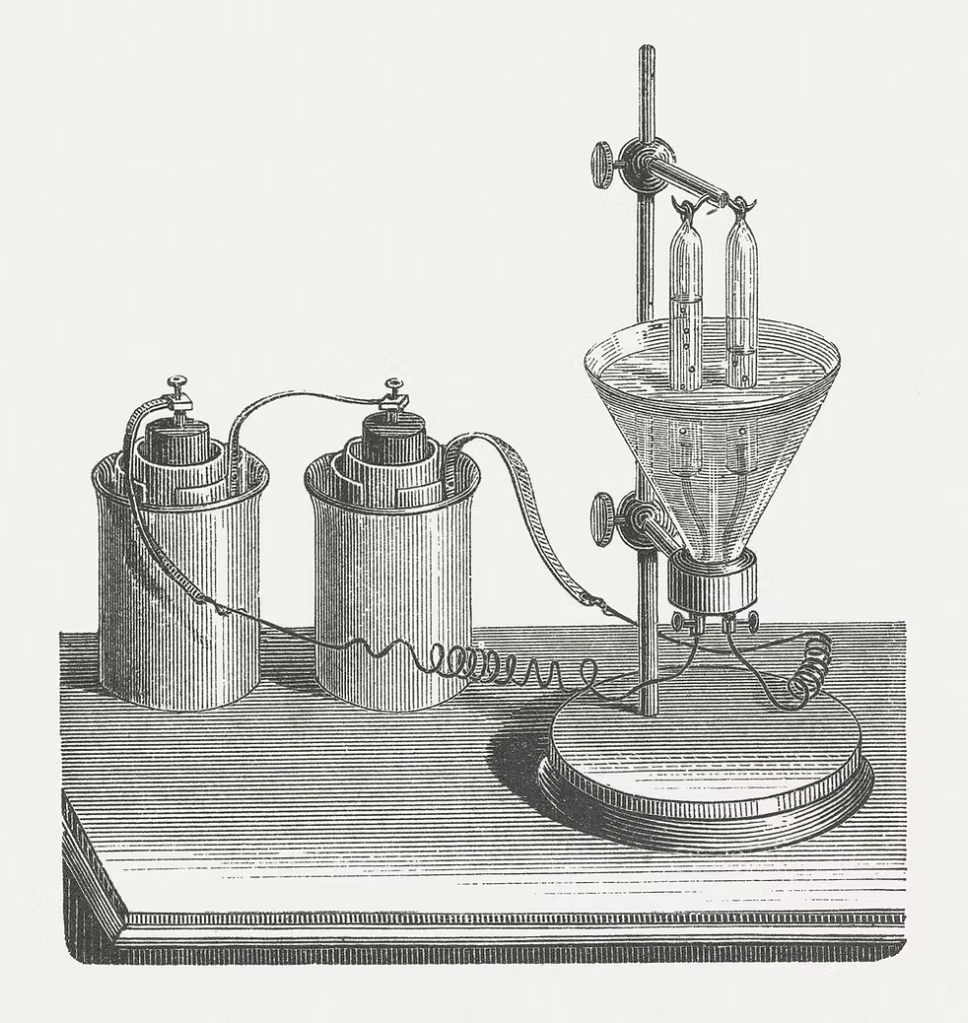

Early water electrolysis experiment in a laboratory, 1864, from Zöllner

Before chemistry became numerical, before pH was measured, knowledge was gathered through slow observation of chance and change. Early natural philosophers worked without meters or scales. Instead, they relied on what matter revealed when placed under various conditions: its shifts in colour, smell, texture, and vitality. Colour was not solely an aesthetic feature— it was a changing state of matter. A signal drift.

Plant dyes played a central role in this way of observing. Extracted from flowers, lichens, roots, and leaves, these pigments acted as responsive substances. Changes became visibly when various substances were exposed to acids, alkalis, fermenting spirits, or mineral waters. The same violet infusion might redden in one context, darken in another, or lose its colour entirely — each transformation interpreted as a sign of a possible underlying force. What we now call “acidity” was once viewed as sharpness or strength.

The red cabbage indicator is made for slow and careful observation. The anthocyanins extracted from the cabbage respond to proton concentration by altering their molecular structure. This alteration produces a cascade of colours. In modern terms, this is pH sensitivity. In older terms, it is matter showing its temperament. The liquid does not measure things; it reacts to stuff. Figures like Robert Boyle used plant-based dyes to systematically distinguish acids from alkalis, formalising colour change as experimental evidence. Boyle’s work marks a transition: colour becomes data, but it remains relational and embodied. Boyle’s instruments are still organic where the slow perception of the event is still central.

The red cabbage experiment reenacts this method. The cabbage — once a living organism regulating its internal pH through vacuolar chemistry — becomes a detached sensing organ. Its pigments, evolved for protection and signalling, are repurposed as a biological interface between environment and observer.

What emerges is a form of knowledge that is qualitative, relational, and interpretive. The meaning of the colour depends on context, comparison, and attention. There is no single “correct” reading without reference — just as early practitioners understood.

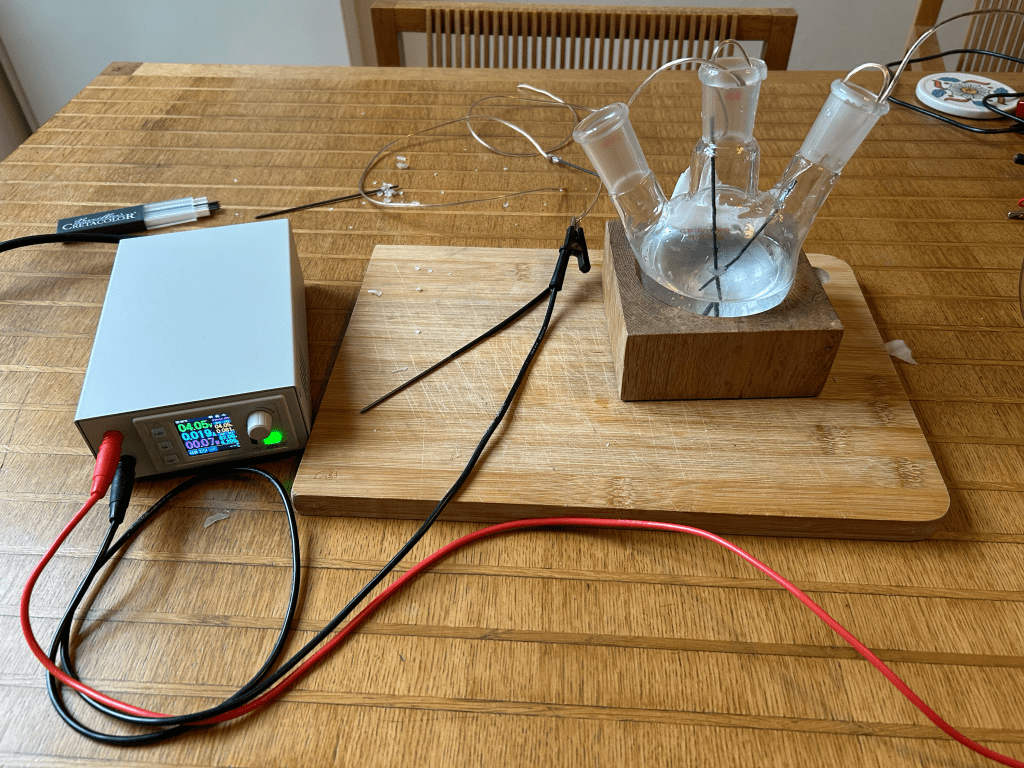

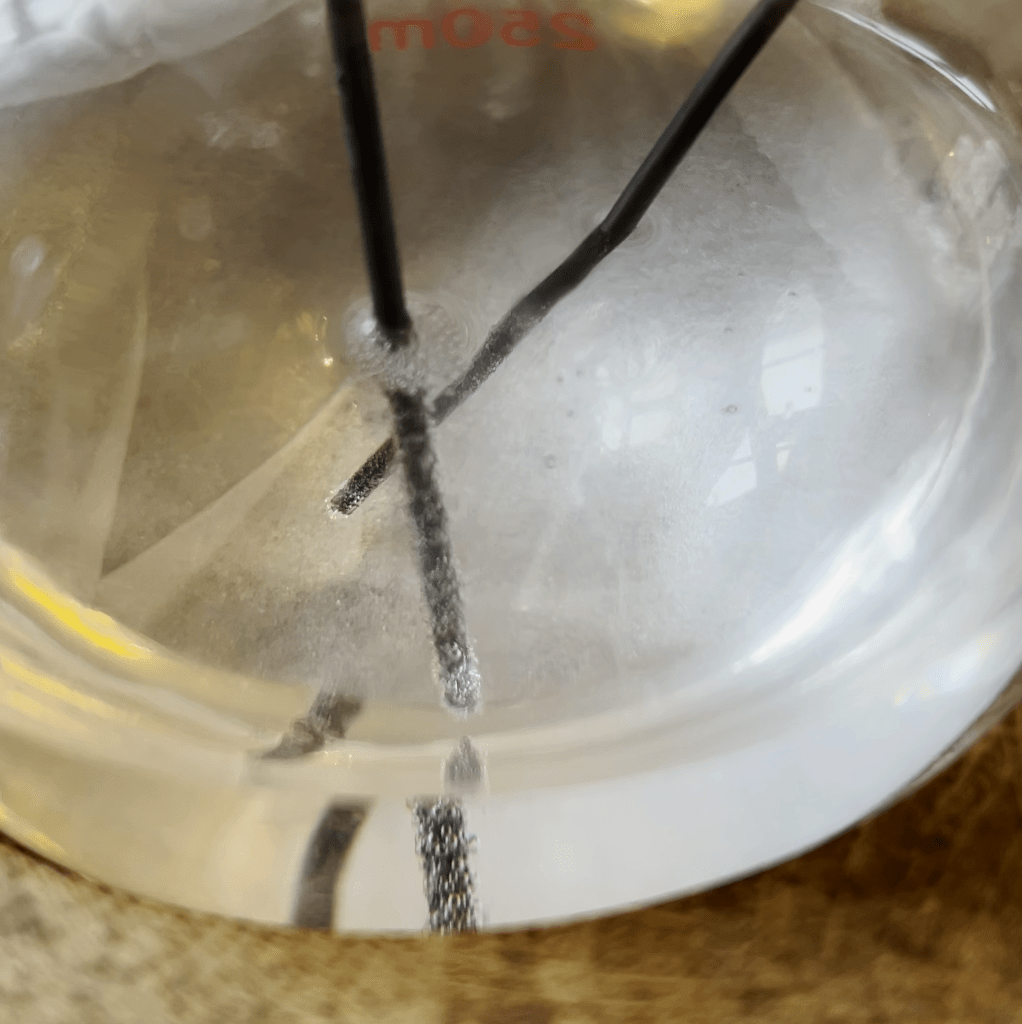

Preliminary experiment: electrolysis of salt water.

The bubbles in salt water are the visible sign of electrolysis: the applied voltage drives current through the solution, causing water to split and form gases at the electrodes (mostly hydrogen at the cathode and oxygen at the anode), which appear as bubbles. Salt makes this easy to observe because it provides ions that lower resistance and increase current, so bubbling happens readily at low voltage. Electrolysis also creates local pH changes—more basic near one electrode and more acidic near the other—which is exactly the mechanism that will produce colour changes when we switch from salt water to a red cabbage (anthocyanin) indicator, where the bubbles will be subtler but the chemical meaning will be visible.