Sensing hybrid forms of organisms, stuff, and tech.

Experiments in process:

Ambix, cucurbit and retort of Zosimos from man. Paris, Grec 2327 fol. 83v.

Not all uses arrive as proofs.

The ideological turn in modern science marked a rejection of an older, organic view of the universe. These ideas are not treated as speculative methods; they actively shape how systems, data, and technology are approached in these experiments. Organisms are treated as non-optimised systems. They are self-organising entities with their own internal rhythms, logics, and forms of expression. When signals from plants, fungi, soil, or sound are translated into images or music, the goal is not to impose structure from the outside, but to listen for patterns that already exist and make them perceptible. By using machines as listeners rather than masters, the work resists the modern tendency to treat life as mechanical and instead returns to an older, organic view of the world—one in which matter is active, relational, and always in the process of becoming.

In the mid–20th century, science began to be rethought not as a simple march toward objective truth, but as a human, historical, and political practice.

Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) broke with the idea that science progresses steadily by accumulating facts. Instead, he argued that science operates within “paradigms”: shared frameworks of assumptions, methods, and standards. Most scientific work, what he called “normal science,” happens inside a paradigm, solving puzzles it defines. But when anomalies accumulate—things the paradigm cannot explain—a crisis emerges. Eventually, a scientific revolution occurs, replacing the old paradigm with a new one that reorganises what counts as a fact, a problem, and even reality itself. For Kuhn, scientific change is not purely rational or linear; it involves shifts in worldviews that are partly social, psychological, and historical.

Paul Feyerabend pushed this critique further and more radically. In Against Method (1975), he argued that there is no single scientific method that guarantees progress. Looking at history, he showed that major breakthroughs often violated the rules that philosophers claimed science should follow. For Feyerabend, methodological pluralism—“anything goes,” as his slogan is often simplified—was not chaos but freedom: a way to prevent science from becoming dogmatic. He warned that treating science as the only legitimate way of knowing turns it into an ideology, suppressing other forms of knowledge such as indigenous practices, art, myth, or embodied experience.

Donna Haraway reoriented these debates toward questions of power, embodiment, and responsibility. In essays like “Situated Knowledges” (1988), she rejected both the fantasy of total objectivity and the relativism that says all perspectives are equal. She argued that all knowledge is “situated”: produced from specific bodies, histories, technologies, and social positions. The problem is not having a perspective, but pretending not to. Claims of “view from nowhere” hide the fact that science has often spoken from very particular standpoints—frequently white, male, Western, and institutional—while presenting itself as universal. Haraway called for accountable objectivity: knowledge that openly acknowledges where it comes from and whom it serves.

Bridging these thinkers, we see a gradual shift. Kuhn shows that science changes through historically contingent paradigms rather than pure logic. Feyerabend exposes how rigid ideas of method can become oppressive and creatively sterile. Haraway then asks: who gets to define paradigms, methods, and facts in the first place—and at whose expense? Together, they transform science from a neutral mirror of nature into a dynamic cultural practice, shaped by conflict, creativity, bodies, and power, and therefore carrying ethical and political responsibility along with epistemic ambition.

Seen from within the field of art, these works reflect on their own conditions of making. They move gently away from the idea of the artist as a single author, and instead look for forms of agency that are shared among organisms, machines, and environments. Rather than chasing novelty or spectacle, the work is guided by a daily curiosity toward slow rhythms, subtle patterns, and personal ways of sensing. This curiosity is not presented as a pure or neutral stance, but as something shaped by tools, habits, limits, and choices, and an awareness that these are always partial.

In this sense, the practice can be thought of in relation to what Thomas Kuhn called “normal science.” Much of contemporary art operates within relatively stable conventions about authorship, objects, exhibitions, and value. The art world shares assumptions that quietly define what counts as a “successful” artwork. These conventions function like a paradigm: they organise expectations about form, circulation, and legitimacy. The prevalent idea of artworks as finished objects that must arrive in the right forms and the right places belongs to this contemporary paradigm. These experiments introduce small tensions within this paradigm by staying close to process, listening, and transformation as ongoing states rather than aiming for fixed outcomes.

These tensions are, however, not seamless. They appear as frictions: works that are hard to fix into stable formats, processes that even resist clear documentation. Collaborations are introduced that complicate authorship, and they generate outcomes that may not fit easily into existing institutional rhythms. In this way, the practice acts less like a new system and more like what Kuhn would call an anomaly: something that does not quite sit comfortably within prevailing expectations.

Experimenting with plants, electricity, soil, and sound becomes less a matter of taking from these ‘materials’ than of being with them, but this “being with” is not imagined as innocent. Listening is always mediated by sensors, software, aesthetics, and decisions, and translation always changes what it receives. Power does not disappear simply because attention becomes more careful. These works therefore try to hold together two positions at once: a desire for relation rather than mastery, and an awareness that these relations are never symmetrical, transparent, or free of constraint.

From the perspective of Paul Feyerabend, this practice would not need to justify itself by appealing to a single correct method or model of legitimacy. Its strength would lie precisely in its refusal to follow a fixed rulebook. By mixing listening, sensing, aesthetics, machines, and nonhuman agencies in ways that do not fit established categories, it affirms methodological pluralism: the idea that creative and critical work advances not by obedience to rules, but by inventing, bending, and sometimes breaking them. Rather than aiming to replace one paradigm with another, such a practice would simply insist on the freedom to work otherwise—and on the value of keeping many ways of making, knowing, and sensing alive at the same time.

From Donna Haraway’s perspective what matters is not resolving complexity, but remaining with it. These works do not try to rise above their conditions or speak from nowhere. They show where they are speaking from: through specific bodies, tools, technologies, and relations. Knowledge here is situated, not universal, and made inside messy, ongoing entanglements.

In Haraway’s sense, “staying with the trouble” means not seeking purity, innocence, or final solutions. It means working inside damaged, uneven, and unfinished worlds, and taking responsibility for how one participates in them. The machines, systems and organisms in these works are not separate actors, but part of the same thick web of relations. Making art becomes a way of learning how to live with these entanglements.

Responsibility therefore is not abstract. It is practical and ongoing. To work in relation is to notice what each choice enables. It is to ask what kinds of futures are being rehearsed through these practices, and for whom. In this way, the work is not only about shared agency, but about shared trouble: about learning how to think, sense, and act together in a world that cannot be made simple.

Imaginary methods and unthinkable Matter

“… I pride myself in being a hunk of lead. Standing dull-eyed and slobbering in the rain of theory, I open an umbrella that protects me from the least drop of insight.” Pataphysica 2, Dr. Faustroll, 2004

The experiments in this book unfold at a different edge of what can be known. Validity is not measured solely through reproducibility or usefulness—though these still play a role—but through the capacity to open up imaginary solutions. Accuracy is therefore not abandoned, but reoriented. Processes are allowed to develop unevenly, without being forced into stable or final outcomes. What matters then is not optimisation as such, but how the experiments in this book gesture toward relations that foster uneasy articulation. These relations are often imperceptible, unthinkable, or that hover at the edge of the imaginary as unthinkable matter.

This approach resonates with pataphysical thought in its quiet resistance to linear problem-solving. Alfred Jarry’s description of pataphysics as “the science of imaginary solutions” points toward ways of knowing in which transformation takes place through indirection, deviation, and sustained attention. Similar methods can be sensed in alchemical practice, where knowledge emerged through working alongside materials, tools, and processes in the workshop. Alchemical knowing developed through vessels, furnaces, residues, and repeated trials—settings in which matter could be observed as it changed state, behaved unpredictably, or resisted control. These operations were inseparable from their imagery: diagrams, symbols, and allegorical figures did not merely illustrate ideas, but functioned as working tools that shaped how experiments were carried out and understood.

The studio then becomes a contemporary laboratory: a space where materials, machines, and symbolic systems coexist, and where knowledge emerges through situated practice rather than through linear explanation.

This operational mode reopens a historical continuity that modern science largely severed. Early modern figures such as John Dee or Paracelsus operated within hybrid systems where mathematics, medicine, and material practice were inseparable. Their work blurred the boundary between empirical observation and symbolic imagination, treating diagrams and analogies as operative tools rather than metaphors. From a contemporary perspective, these practices can be understood as proto-pataphysical: not as severed, naïve precursors to today’s science, but as alternative ways of knowing that cultivated coupling the real and the imaginary.

Revisiting these traditions offers a way to question the ideological assumptions embedded in contemporary scientific and technological systems. Research-creation, informed by alchemical and pataphysical thinking, instead foregrounds uncertainty, doubt and transformation as legitimate practices. It is from this position that the ideological turn of modern science can be critically re-examined, and alternative ways of listening to the world can open up.

Giving stuff a voice.

Patiently observing magnetic oil swirl and react in unexpected ways, or hearing sound be intercepted by a single salty drop of water, are humble studies. They do not require expensive lab gear. Spending time carefully exploring these simple processes set into motion—while resisting the urge “to solve a puzzle” however, becomes an experiment in and of itself. The paradigms of science and art often pull us in different directions: either toward methods that solve scientific “puzzles,” or toward aesthetics that seek meaning by aligning with the dominant art trends of the moment. Attempts to bridge subjective experience and objective study, however, arise naturally. We oscillate between feeling and noticing. Seeing patterns, and sensing the whole reflected in each part, is not a specialised skill—it is part of our daily goings on. We do it when we spot a mood change in a cat or when we sense a change in someone’s voice. These quiet acts of noticing are how we interface inner experience with the outer world. There is no imposed hierarchy when we react to the environment like this, the one seems to flow into the other fluidly. This way of noticing becomes participation. It is less about control and more about interfacing and relating with the world. Rather than solely extracting meaning, the emphasis lies in letting experience unfold. The noisy complexity and uncertainty connecting inner notions and outer processes is our daily interface.

The animated processes we will observe are expressive and appear to display characteristics often associated with living systems. While we know that motion alone cannot be considered a definitive sign of life, the material world around us is constantly engaged in the transformation of energy. Sometimes this transformation unfolds at an almost imperceptible pace, as in the slow decay of wood; at other times it occurs through computational processes, unfolding in abstract but equally dynamic ways. The observations gathered in this book move fluidly between physical matter and virtual matter. The simulations used in these experiments are not merely representations but active tools for thinking, helping us trace how natural processes might operate in the real world. This dialogue between computation and nature has deep roots: Alan Turing, for example, linked artificial intelligence with biological growth in two seminal works—his 1950 paper on machine intelligence and his 1952 paper on morphogenesis.

Across these pages, the boundary between the living and the simulated is intentionally unsettled. By placing material transformations alongside computational ones, the work invites us to consider life not as a fixed category but as a spectrum of processes. Some processes are chemical, some mechanical, some algorithmic, yet they all organise energy into form. Whether rotting wood, reacting chemicals, or evolving code, each system reveals patterns of change that echo one another. In this way, the book does not argue that simulations are alive, but that they allow us to see more clearly the logics by which life-like behaviours emerge and transform.

The series of experiments presented here are closer to investigation, performance, and craft than today’s standardised so called lab experiments. Early, natural philosophers or protoscientists are an inspiration for this series. Protoscientists’ observations and experiments were part science, part spectacle, often done in theatres or lecture halls. The early labs looked more like craft spaces mixed with libraries and cabinets of curiosities, not unlike how an artist studio might look today. Before science became an industry of results, it was a cultural practice. Figures like Humphry Davy did not merely publish findings; they staged investigations before audiences, mixing curiosity, spectacle, craft, and thought.

Furthermore, early experimenters wrote in personal voices, admitted uncertainty, and treated wonder as legitimate. Reviving this tone counters today’s hyper-optimised, metric-driven culture of productivity. It makes room for slow thinking, emotion, narrative, failure, and intuition.

Calling experiments “inquiries” or “practices” rather than technical procedures makes them accessible. Experimentation becomes something anyone can attempt, not only trained specialists. This supports citizen science, artistic research, DIY labs, and community workshops—spaces where curiosity matters more than credentials.

There is also the question of play. Early experiments were risky, joyful, and sometimes theatrical. They welcomed speculation and “useless” trials that later proved essential. Restoring play to experimentation would encourage creativity, allow mistakes, and support ideas that don’t fit immediately into marketable design options or data build-up.

Romantic engineering.

Consider these three sentences:

Do we always have to proof our findings?

First-person experiences are not mere noisy artefacts.

Imagination is a legitimate instrument of inquiry.

The statements above are often vulnerable to being dismissed as merely “poetic” or “artistic,” rather than being taken seriously as rigorous forms of inquiry. This dismissal typically rests on the assumption that subjective approaches lack structure, reproducibility, or functional value. However, the experiments presented here argue the opposite: subjective experiments can possess strong disciplinary qualities precisely because they attend to how, when, and under what conditions phenomena appear.

Rather than treating subjectivity as taboo, these experiments explicitly embrace the situated nature of perception, aesthetics and experience into their intent. They register not only outcomes, but also the temporal, contextual, and messy sensorial dimensions through which those outcomes might emerge. In this sense, subjective experiments do not abandon rigour; they relocate it.

These subjective or romantic experiments operate across aesthetic, sensitive, and functional dimensions of experience. Aesthetic qualities shape how phenomena are perceived and interpreted. Sensitive qualities account for affective and embodied responses. Functional qualities describe how these experiences interact with systems, tools, or practices. Together, these dimensions form a coherent framework for evaluating subjective findings—not as arbitrary impressions, but as structured observations grounded in experiential conditions.

Contemporary science often treats proof and objectivity as moral imperatives, as if phenomena only exist once purified of observers, context, and history. Whatever does pop up during so called “objective” experiments that is unproven or erroneous, is deemed to be labelled as a dreaded artefact. Scientists distinguish artefacts from genuine findings to ensure the validity and accuracy of their results, preventing wasted time chasing false findings. This is a valuable method, for sure. However, in doing so, a lot of useful cultural, personal, aesthetic and scientific information is often disregarded or even ignored. Therefore the path to find and experience things, narrows.

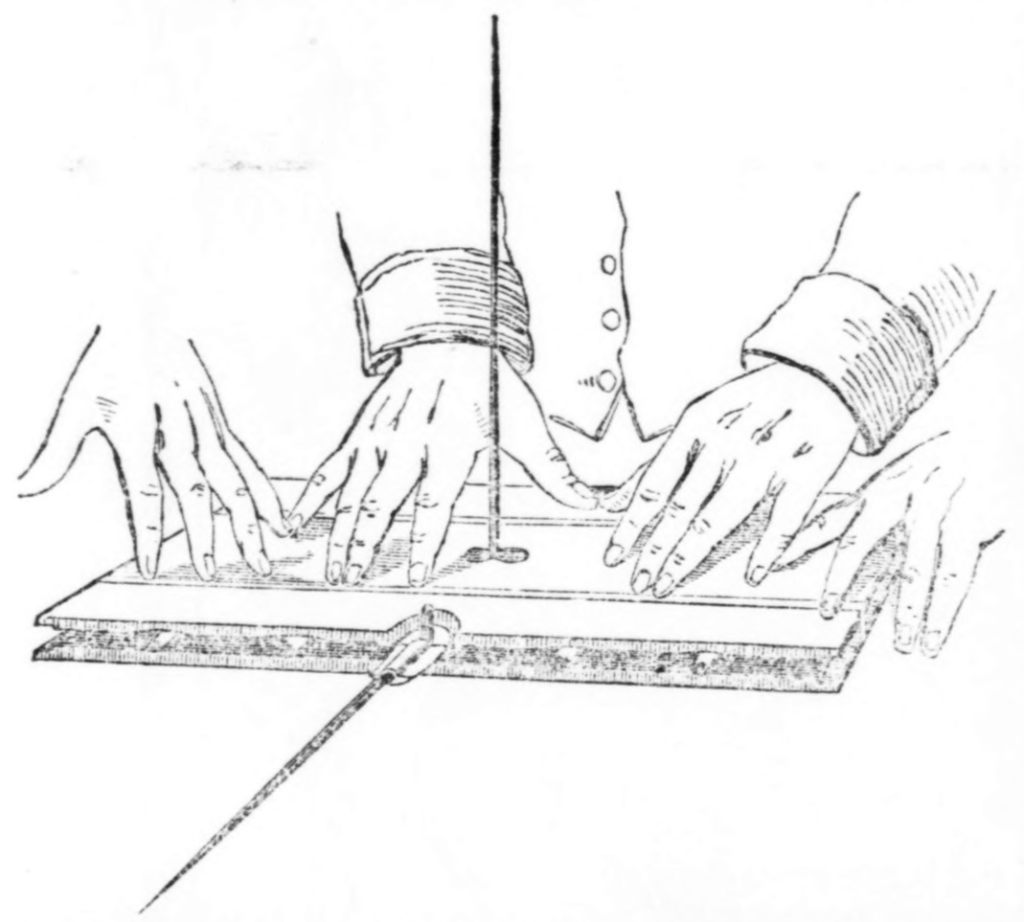

Faraday apparatus for ideomotor effect on table turning.

“Science” was not always like this. Natural philosophy felt it belonged to the world. Today’s predominant stance that intelligence is something exclusively human was alien to them. Its methods were observational, speculative, and materially twined. Romantic knowledge arose not from isolation of nature, but from prolonged attention, repetition, and experiment within living systems. Natural philosophers tuned themselves to rhythms and anomalies—weather, growth, decay, resonance—treating plants, soils, fluids, and atmospheres as collaborators rather than inert objects. In this sense, their practice aligns with these experiments. Sensing infrastructures become instruments of listening rather than functional control. Data streams behave like ecological signals rather than abstractions. Computation operates as a form of extended perception allowing senses to meld or interface through coupling machine learning, signal analysis, and generative systems to plants, fungi, viscous fluids, and sound. Natural philosophers did not so much ask what intelligence was, but where and how it appeared, how it drifted, and how it might be sensed when nature is the sole measure.

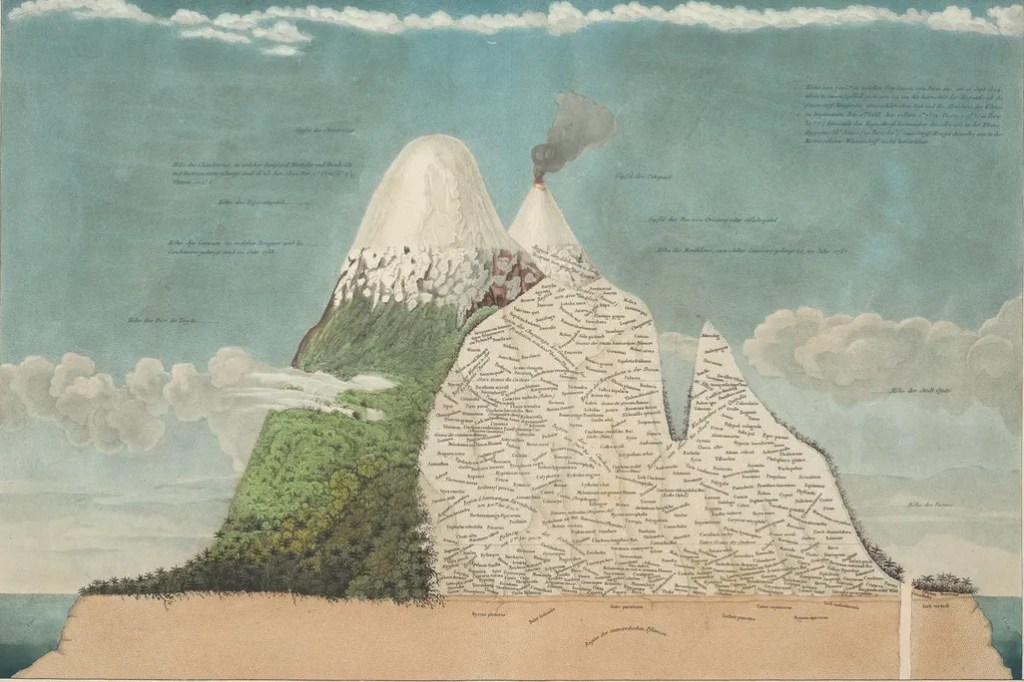

Von Humboldt, Geographie der Phlanzen in den Tropen-Ländern.

Romantic science tried to remember this. It tried to recall older ways of experimentation that had been eclipsed by the drive toward reduction, measurement, and mastery. Where Enlightenment science increasingly isolated variables and stripped phenomena into parts, Romantic science turned back toward wholeness, correspondence, and lived encounter. Figures working in this mode treated nature not as a mechanism to be dismantled, but as a dynamic, self-organising field whose forces could only be understood through participation, intuition, and aesthetic sensitivity. Observation was inseparable from affect. Imagination became a legitimate instrument of inquiry. This shift resonates with these experiments, where signals are not reduced to noise-free utilities but allowed to remain ambiguous, expressive, and relational. By working with biological data, environmental fluctuations, and generative systems as co-evolving processes, the experiments echo Romantic science’s refusal to sever feeling from knowing, and its insistence that understanding emerges not from trying to control nature, but from attunement to its unfolding patterns.

From this perspective, the experiments presented here are a critique of contemporary culture and science’s blind faith in proof, functionality and objectivity. Proof assumes repeatability without history, observation without consequence, and systems that can be reset. Yet the experiments demonstrate that some phenomena only exist through duration, noise, asymmetry, and participation. What they show and produce are not falsifiable claims or artefacts but situated knowledges. The goal is to allow an understanding of how matter, observer, and machine co-evolve through feedback.

Not all truths arrive as proofs. Some arrive as sustained encounters, where coherence replaces certainty, and engagement reveals more than detachment ever could.